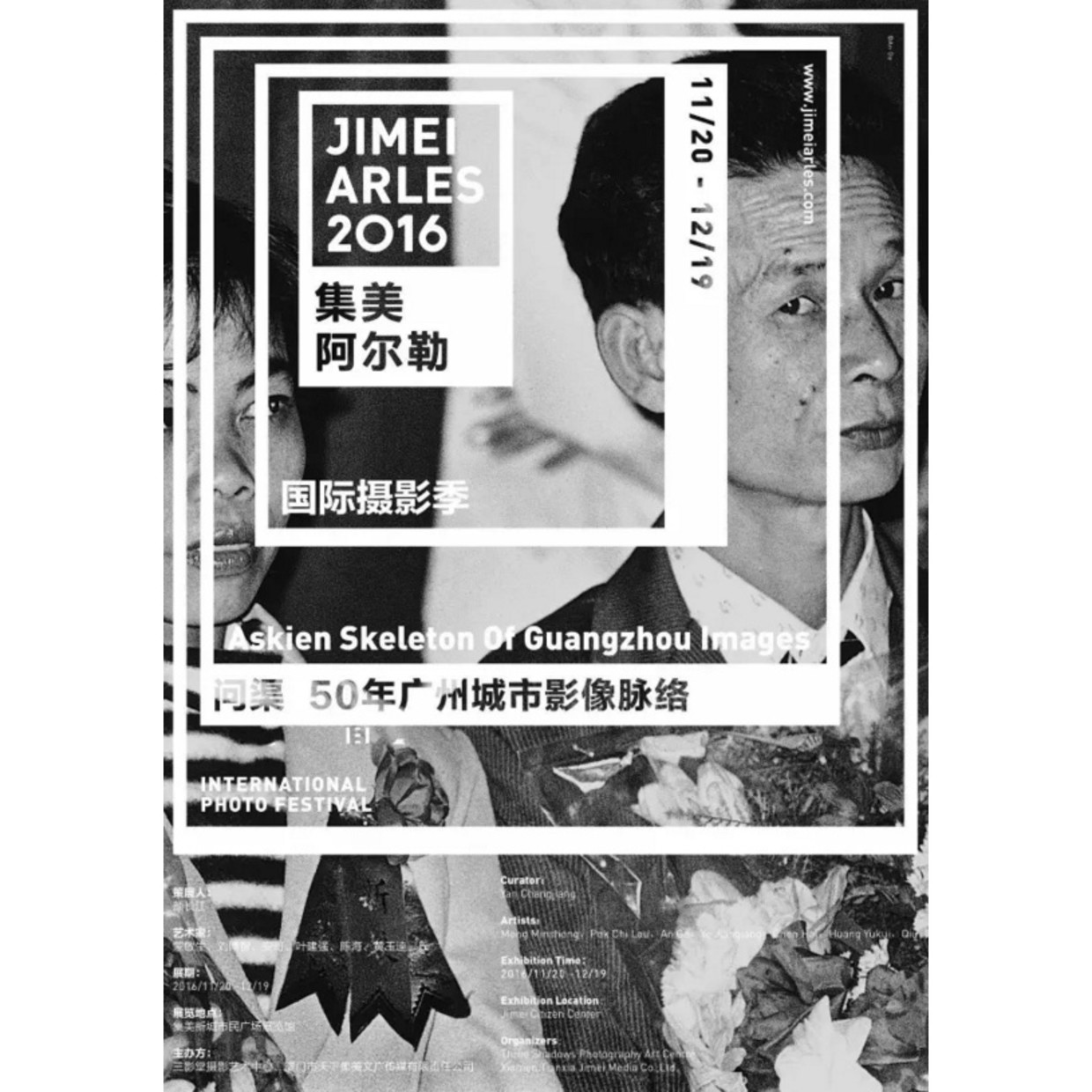

Yan Changjiang: Askien – Skeleton of Guangzhou Images

Askien - Skeleton of Guangzhou Images showcases the immense changes that the city of Guangzhou has experienced over the last fifty years, through the work of these seven outstanding photographers. This exhibition is about contemporary photography, but also about photography as an art form.

This nearly fifty-year period contains both the Cultural Revolution and Reform & Opening, and it is the second half of one hundred years of spectacular change in China. This period presents the formidable process of incredible transformation. Since the beginning of history in China, there has been systemic and cultural consistency, but these fifty years have shifted that paradigm, and we have truly entered into modern society. Therefore, the once-in-a-millennium change that we have just undergone makes us part of a grand era, which may have a deciding impact on world history. Naturally, promptly delineating and summarizing this period is very important.

Photography is naturally the most important way to depict and summarize this change. We have extended the conventional historical reach from Reform & Opening (as in An Ge's work and exhibitions) back to the Cultural Revolution. The reason is very simple: if we do not examine what came before and after, it is difficult to understand the major change that took place. This will finally help us understand the larger meaning of Reform & Opening.

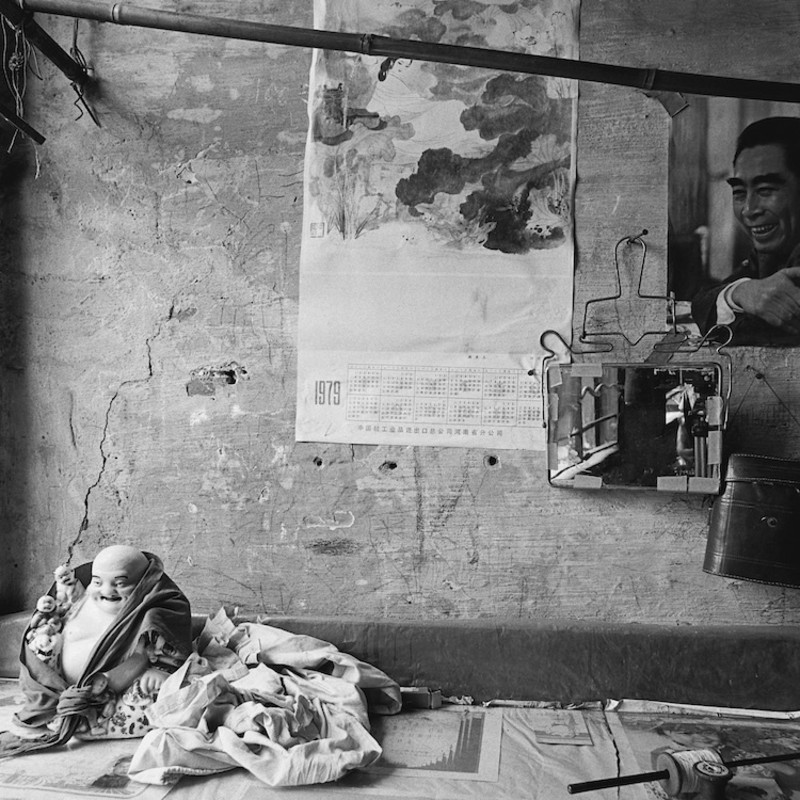

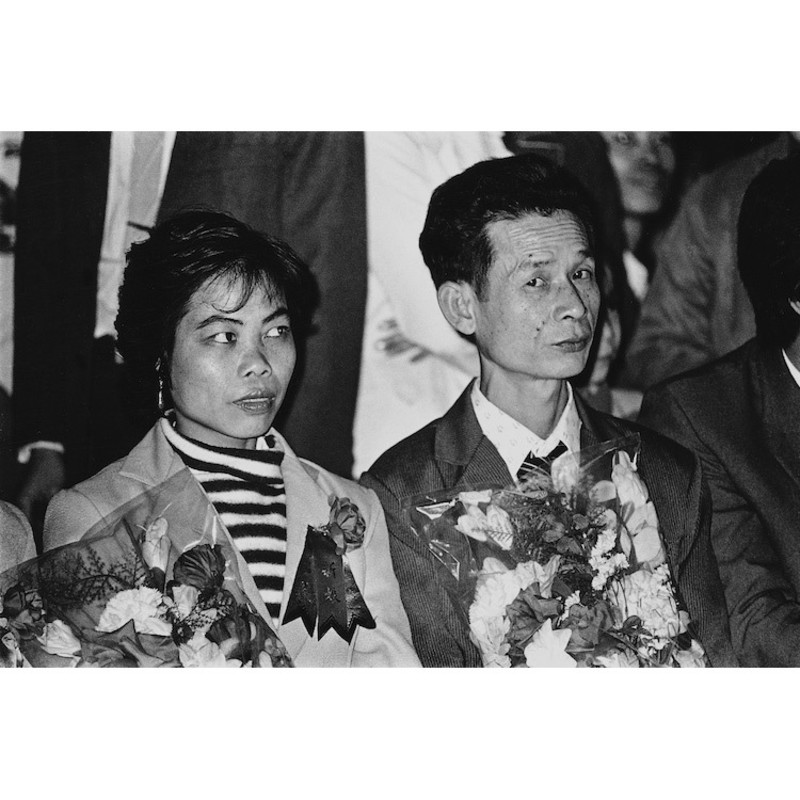

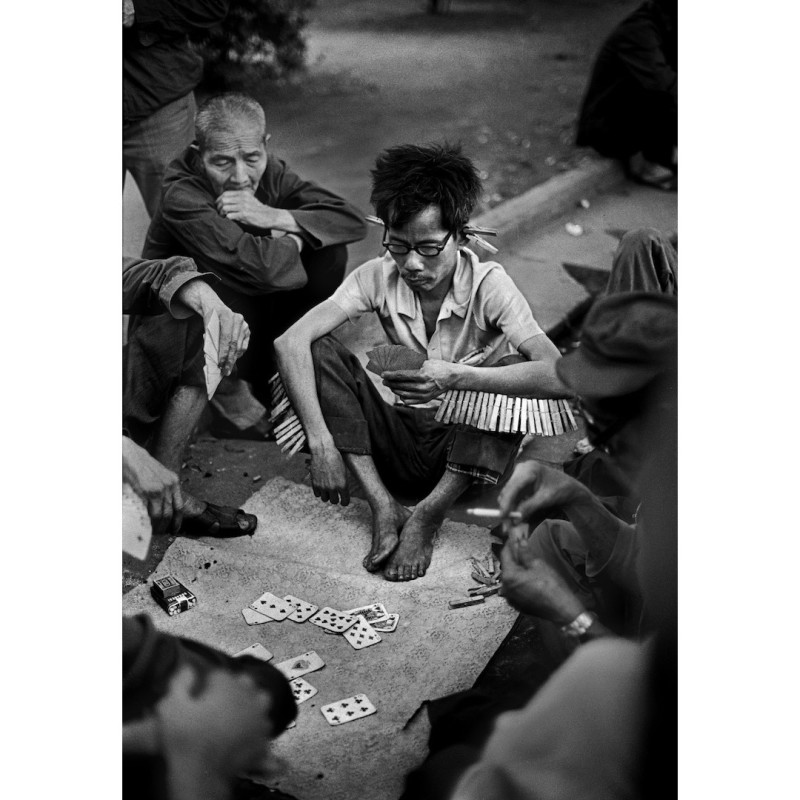

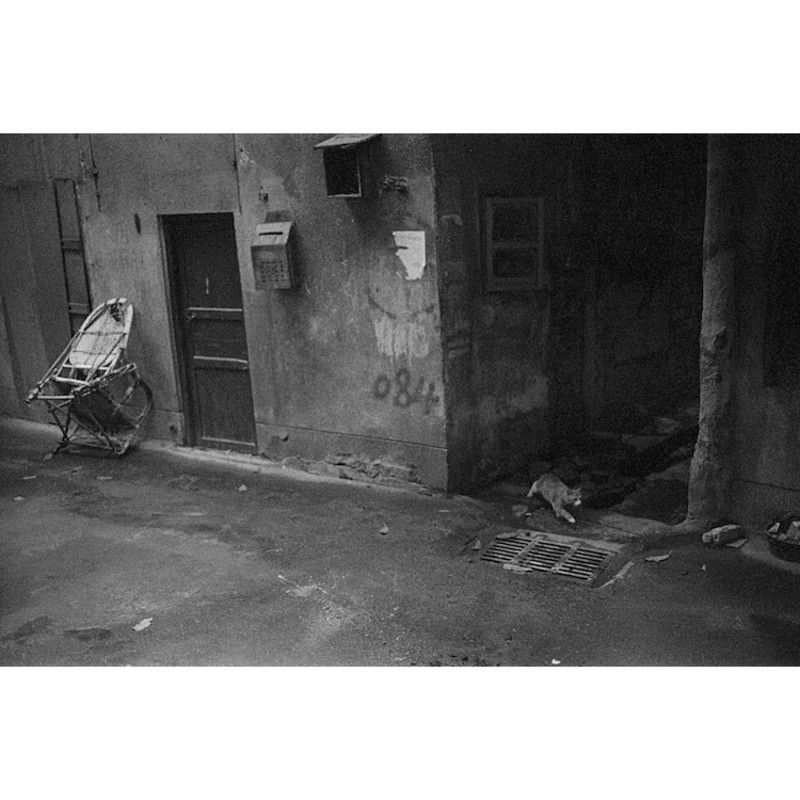

In addition, we did not select illustrative pictures, like the images that would have been used in a display at a history museum or a tourist site. These are truly individual works by photographic artists. In documentary photography, the subject matter captured by the photographer's lens will be illustrative, but it is a distinct kind of illustrative. In contrast to the photographers in photo studios, they must have a view on reality that informs their overall feeling about the city. These photographs, full of emotion and judgment, may not be intensely functional, but they narrate the spiritual history of the city. This history may be deeper, more accurate, and more subjective; it is certainly closer and truer. Their subjective observations actually constitute a more objective history.

Good photographers think independently. Their observations do not serve any external power; they simply believe in their vision, closely examining life. An Ge, Pok Chi Lau, Ye Jianqiang, and Chen Hai are masters of careful observation, a skill that is often ignored by illustrative photographers, so art photographers may better represent the truth of history. This new vision of history stresses the details of life, showing that the daily lives of ordinary people are the true stuff of history. These photographers are good practitioners of this idea.

This is a history of everyday life, but I also think it is a history of art. The history of artworks, and particularly the history of photographs dealing with daily life, reveals and distills the manners and morals of the time and the essence of the region. That is to say, these photographers are always seeking the soul of the city. After ten or twenty years, we very easily see the "history of the soul" in their pictures. Of course, for viewers, this is an entirely new experience. There are no massive political rallies or grand personages; you appreciate history through the food, clothing, housing, and actions in the pictures, as well as the myriad expressions on people's faces. This historical experience has many facets, which rescue our minds and senses from complete alienation.

In the planning process, I was dismayed to find out how few good photographers there are, and that even fewer have photographed a single city over a long period. In contemporary China, photography has always had deficiencies, from the low-quality of amateur culture, to the lag in conceptual photography, to the bifurcation of salon photography and propaganda. Now, everyone has a camera, but the lack of good urban photography turns out to be a national phenomenon. I once wrote an essay entitled "Guangzhou Needs Its Own Photography Spokesperson" because it is really hard to find satisfactory bodies of urban photography that are comprehensive, prolonged, and reflect some cultural consideration. The situations in Beijing and Shanghai are not much better, giving you the feeling that Chinese photographers are somehow wasting their youth; the sources of urban photography are disappearing, and history is disappearing. I have found these six, and I thought that bringing them together for this kind of exhibition would work. This exhibition and catalog will likely become part of the history of Guangzhou photography exhibitions. Guangzhou has never had an exhibition that reviews the history of the city through the work of art photographers. The renovated old space in which the exhibition has been held is distinctive, but more importantly, the show returns images of old Guangzhou and its residents to the old city; this is an immensely meaningful event. To a certain extent, this exhibition is a reincarnation of old Guangzhou, collectively speaking for this old city. Times have changed, and traditional styles and cultural values have become rarer and more precious. We hope that we can discover, present, and capture the soul of Guangzhou. This is just a small way to repay the great city that nurtured us.

I am old friends with these photographers, and I am delighted to be able to bring all of these wonderful people together. This is the first time that An Ge and Ye Jianqiang have been exhibited together, despite having been so influential for their photographs of the average people of Guangzhou. We are primarily considering the works of these famed photographers from an artistic perspective, and not as the mechanical representation of points in history. We have only chosen four of Meng Minsheng's photographs from the Cultural Revolution, which indirectly and intelligently reflect that time. We have chosen Pok Chi Lau's photographs of family life during the planned economy period, which also precisely present the marks that the Cultural Revolution left on the post-Cultural Revolution world. In addition, Huang Yukui, Chen Hai, and Qiu, as the new generation of photographers (at least in terms of when they entered the profession), are immensely individualistic and open-minded; they contrast wonderfully with the pictures taken by their photographic elders, and the first presentation of these images is one of the highlights of the exhibition. The exterior and interior design of the building that is hosting the exhibition is very distinctive; when these elements combine with the artworks, they produce deeper meaning and greater interest. Artworks do not exist in a vacuum; they become more valuable in combination with their setting, and this is clearly the most appropriate place for them.

Finally, I would like to thank the organizers, as well as Yan Wendou, Tao Zhenyu, Qiu Junsong, and all of the other hard-working staff. Yongqingfang on Enning Road has been brightened by your diligence. These pictures have returned home, just as we have...