Mastering the parameters of aperture, shutter speed, and ISO is often the first lesson for anyone picking up a camera. Through this learning process, we "tame" the camera and unlock visual effects that our naked eyes cannot perceive—such as the exaggerated bokeh of a wide-aperture lens, the breathtaking starry skies captured by high-ISO cameras, or the motion trails recorded by slow shutter speeds. The thrill of capturing such images for the first time inspires us to plan more journeys and shoots, longing for even more extraordinary photographs.

This classic narrative of humans mastering cameras, however, raises an overlooked question: Are we taming the camera to create these visually arresting images, or is the camera taming us — commandeering our language and ensnaring us in its logic?

This paradox haunts Su Zhongyao, a photographer who views the camera as a ritualized technological "black box." Just as Vilém Flusser described in "Towards a Philosophy of Photography": "In the photographic ritual, humans are, in essence, extensions of the camera." Today, this black box has evolved into an even more complex entity: artificial intelligence.

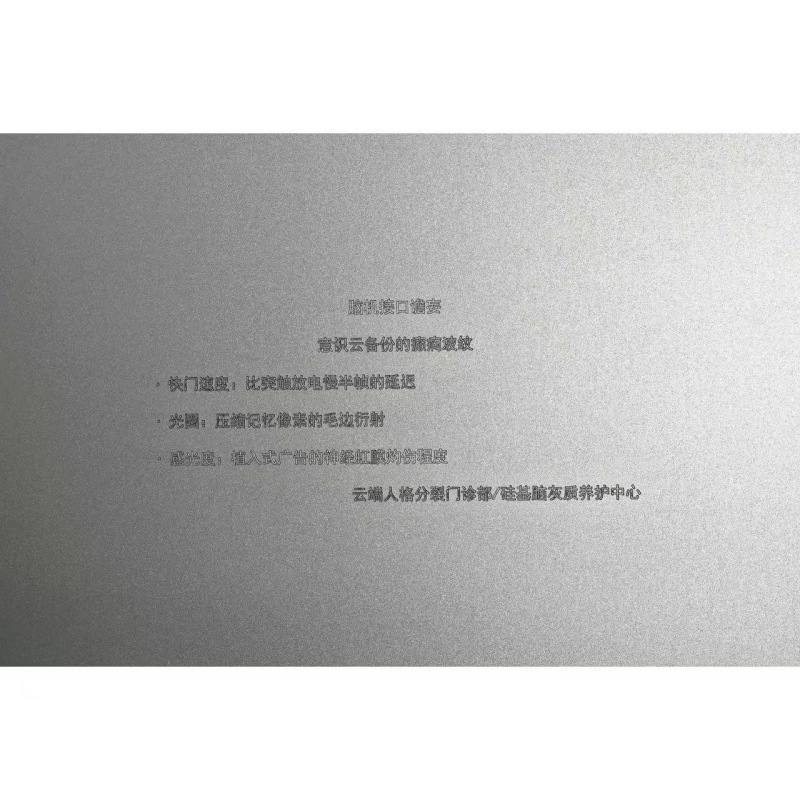

Su’s exploration of "technological black boxes" unfolds in two phases. In his earlier works, he stripped photography of its performative act, replacing camera operation with light-meter readings and linguistic descriptions of imagined imagery. Over time, even physical documentation became obsolete—texts and parameters were conceived purely through imagination, then engraved onto metal plates by hand. In his latest phase, he cedes even imaginative control to artificial intelligence. Parameters are no longer concrete camera settings but abstract descriptions generated by AI. These texts are then carved into aluminum plates via CNC machine tools, transforming speculative ideas into material artifacts.

The resulting artworks form the core of this exhibition, shifting the focus from cameras to the deeper "black box" of AI. When creativity shifts from human to DeepSeek models, the chain linking inputted text and output image fractures entirely. AI no longer produces legible visual correspondences but schizophrenic jumbles of language—a playful yet unsettling echo of Babel’s tower. This reveals the core contradiction between technological black boxes and humanity: the act of "mastering" cameras or training AI models is, in essence, an acceptance of their technical syntax. From this perspective, we ourselves are the speakers colonized by this technological grammar.

The use of inscribed metal plates also evokes ancient "curse tablets" from Bath. Two millennia ago, bathers would carve curses against enemies onto soft lead sheets, tossing them into sacred pools in hopes the gods would punish wrongdoers. Su’s works resonate as a 21st-century palimpsest: the enigmatic, almost "schizophrenic" phrases generated by AI—etched onto gleaming industrial aluminum—read like modern technological incantations.

The mirrored sheen of the aluminum plates metaphorically reflects our relationship with technology: we input commands into the void, yet what returns is a distorted reflection of ourselves—familiar yet alien. Two thousand years later, it seems we are still casting our anxieties onto metal, hoping for answers.

For two millennia, it appears we have been engaged in a perpetual act of reflection.

Text/Li Zijian